Hollywood Magazine (1940) - Personal History of a Foreign Correspondent

Details

- article: Personal History of a Foreign Correspondent

- journal: Hollywood Magazine (August 1940)

- issue: volume 29, issue 8, pages 35-36 & 63

- journal ISSN:

- publisher: Fawcett Publications, Inc.

- keywords: Albert Bassermann, Alfred Hitchcock, David O. Selznick, Edmund Gwenn, Foreign Correspondent (1940), Herbert Marshall, Joel McCrea, Laraine Day, New York City, New York, Osmond Borradaile, Rebecca (1940), Robert Benchley, Secret Agent (1936), The 39 Steps (1935), The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934), Walter Wanger

Links

Article

Personal History of a Foreign Correspondent

Four different times a script was prepared for Personal History. Four different times it was abandoned. Here is why they finally changed the title also, and why they call it Foreign Correspondent

In Foreign Correspondent, Joel McCrea admits that he has the most exciting role of his career. He plays the part that John Gunther, Pierre Van Paassen, Leland Stowe, Jay Allen, Ernest Hemingway, Vincent Sheean and a lot of other swell reporters, who go poking about the world where trouble is the hottest, play in real life.

Sheean, as a matter of fact, is responsible for the whole thing. He wrote the book called Personal History, which Walter Wanger bought over three years ago, and which he has been trying to make into a movie ever since.

The book is the story of Sheean's own adventures as a journalist in a world that has been preparing for Armageddon ever since the Versailles treaty.

Fresh out of college he was sent by an American news syndicate, the Newspaper Enterprise Association, to Europe. His job was to go where world history was being made, watch it and tell about it for the folks back home.

In Spain a censor who didn't like his cables threw him into jail. In Morocco he traveled with Abd El Krim's guerrillas as they battled with Spanish troops. He dressed as a Riffian soldier, dodged rifle bullets and bombing planes and sent back some exciting dispatches to the United States.

Later he went to Corsica, Egypt, Persia, Russia, China, Palestine—wherever history was being made. He saw it all and he saw what was coming, too. His book is packed with the living history of the '30's ... the prelude to the war now raging in Europe.

Wanger knew he had something when he bought Personal History. The book was a notable best-seller. But by the time the first treatment was prepared, it was out-of-date. War in Spain had broken out. That was the logical background for a film about a foreign correspondent. A new script was ordered.

That script, also, was out-of-date almost as soon as it was finished. The war in Spain ended. Conditions in France and Germany changed. A third script had to be discarded when Germany took Austria and Czechoslovakia.

Sheean's adventures in wars he had witnessed suggested a fourth treatment. He came to Hollywood and offered Producer Wanger valuable suggestions and constructive criticism.

You know what happened then:

The Hitler Blitzkrieg drove through Poland. England and France declared war on Germany. Russian soldiers trampled Finland. The fourth script found the wastebasket.

About that time Director Alfred Hitchcock came to Wanger with an entirely new idea.

New alliances form swiftly in war time. Shrapnel and shells that explode into curious bouquets of dust and stones incessantly find fresh victims. People like you and me cower in cellars or run wildly through broken streets and open fields for shelter in holes and ditches while incendiary bombs go on falling, falling ...

Hitchcock's idea was simple. Maps go out-of-date overnight. But the old scheming and plotting—the intrigue of politicians and the makers of wars—don't change. They, like the poor, are always with us ... and that's what Foreign Correspondent will show.

There have been other instances when a best-seller was rewritten entirely for the screen, but I don't believe there's ever been one hammered out of shape four times by the big guns of Europe.

After such drastic changes, Wanger refused to capitalize on the title, Personal History. The book gave him the main idea, but the title, Foreign Correspondent fits in better now. So Wanger courageously forgot the $100,000 he had invested in the book title and went on from there.

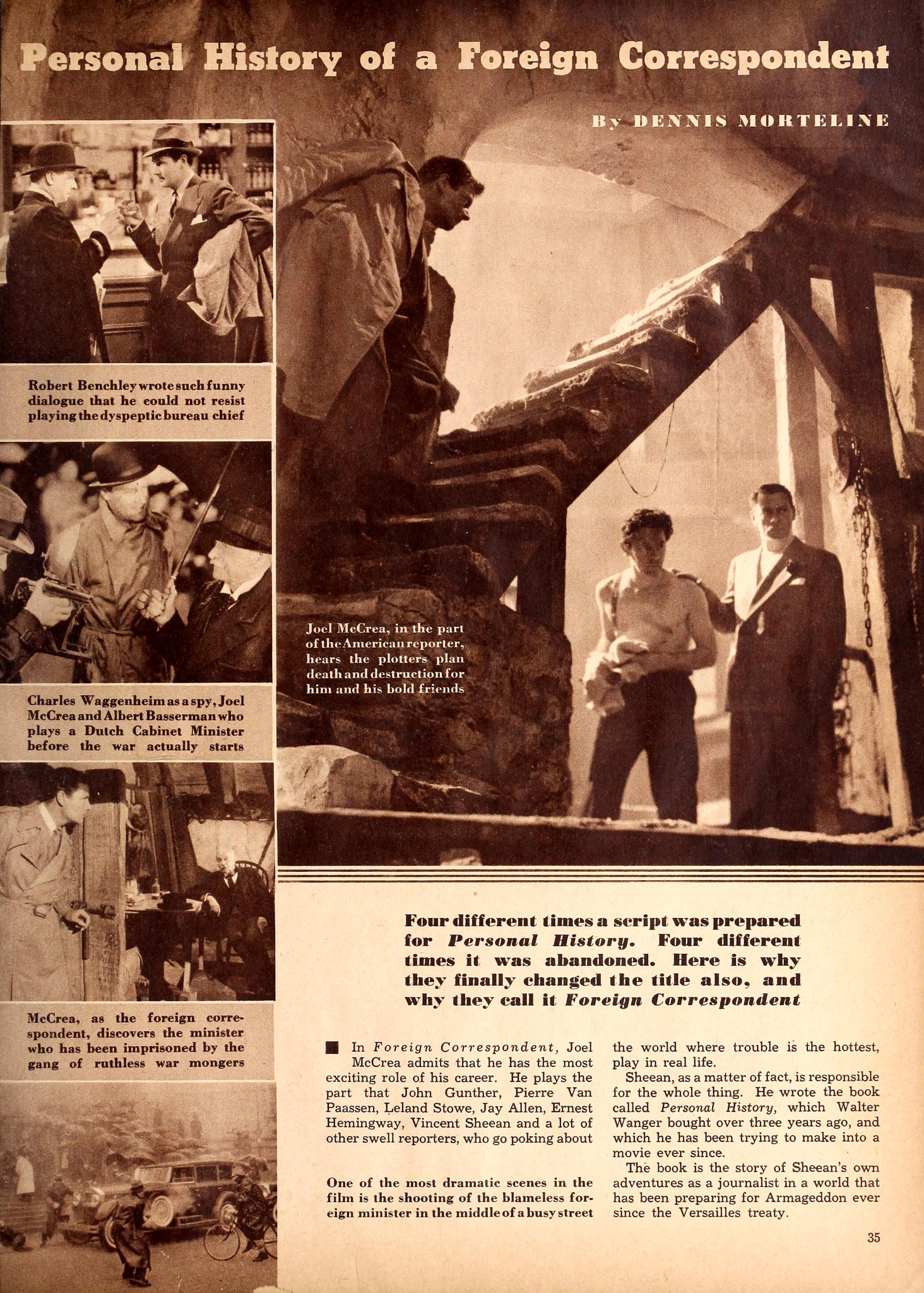

The day I talked with Wanger a couple of the best scenes in Foreign Correspondent were being shot. McCrea, in Holland, on the track of a gang of secret agents, got into a tight spot and had to climb out of his hotel room dressed only in a pair of shorts.

He also had to scale the building and hoist himself into a room just one floor above his own where Laraine Day was entertaining a couple of dowagers.

Joel gets in through the bathroom window, opens the door and peers out. At that precise moment one of the dowagers looks up from her teacup.

The man in shorts was too much for her, too much for her companion; and for that matter, too much for Laraine. Her visitors hadn't thought she was that kind of girl. They were out of Laraine's room in a flash. To them a strange man hiding in a nice girl's bathroom was worse than death.

You will see by this episode that the reporter, was, indeed, in a tough spot. The killers' guns were almost easier to face than the situation compromising to a young girl he'd met only once before.

Besides McCrea, who plays the part of the American correspondent, there's Miss Day, Herbert Marshall, Eduardo Cianelli, Robert Benchley, Albert Basserman, Edmund Gwenn and several hundred others in the cast.

Marshall plays Stephen Fisher, the head of an international peace movement trying to stem the tide of blood in Europe. Laraine is his daughter, Carol. Benchley is Stebbins, the head of the Globe Syndicate news bureau in London. McCrea works for the Globe Syndicate, too, on a roving assignment.

Cianelli (as you might have guessed) is Krug, sinister, deadly leader of the gang that is promoting war. Albert Basserman, the great German stage actor who made his film debut in Dr. Ehrlich's Magic Bullet, plays Van Meer, Dutch minister and ardent pacifist.

Benchley literally wrote himself right into Foreign Correspondent. Hired to write some humor into the otherwise grim script, Benchley made an elegant character out of Stebbins.

When he finished creating the droll, neurotic news bureau manager there was only one man in Hollywood who could play the part. Hitchcock read the script, telephoned Benchley and put him to work as an actor. You've seen him before on the screen, but not in such a side-splitting role.

Laraine was about the busiest person on the set. Every time she had a few minutes between scenes she dashed for the telephone. Once she made connections she engaged in the most baffling conversation I've ever heard, mixing screams and sobs and laughter into her talk. You couldn't help listening.

After a telephone session that lasted twenty minutes she explained that she was rehearsing her part for a play that will be produced by the Wilshire Group Theatre, which is sponsored by the Mormon Church. She is one of the little theatre group's stars, but she can't take time out from Foreign Correspondent to attend rehearsals with the rest of the cast, so she had to do it by telephone. While the others were on the stage across town she was reading her lines over the wire.

Around the adventures of Bill Jones, a man whose knowledge of inside intrigue makes him a likely target for Gestapo gunmen, are scenes filled with excitement and suspense. The chase, the developing love story and the parade of living history moves all over the map. The action takes place in New York, England, Holland, the Atlantic and the North Sea.

Hitchock is the screen's unchallenged master of mystery. He directed The Man Who Knew Too Much, Secret Agent, The 39 Steps and a couple of other blood-chilling pictures in England. Over here he recently finished Rebecca for David O. Selznick.

For such a mild-mannered, fat man, Hitchcock is an amazing person. He says he likes to make the audience suffer. He does, too, but never from dullness. He builds suspense that puts you on the edge of your seat. Part of his technique is to disarm the audience and then, suddenly have that innocent-looking man (the one you wouldn't give a second glance) turn into a cold-blooded, deliberate killer.

To watch him on the set you'd get him mixed up with one of his own villains. His large ears, mild blue eyes, double chin and pink, well-scrubbed cheeks give him a jolly, innocent look. He invariably goes to sleep at Hollywood parties, sits with his hands folded over his paunch. Once his wife woke him up and gently suggested they might as well go home.

"Oh, no," he replied, "that would be rude."

It won't show on the screen, but one of the most exciting things that happened during the shooting of Foreign Correspondent was the adventure of Osmond Borradaile. Borradaile is a location cameraman. Wanger packed him off to Amsterdam, where a large part of the picture takes place, to get background shots.

The Nazis had not yet smashed through Denmark and Norway, but Holland was not exactly what you'd call a homey place when Borradaile arrived. Finally, though, he got all the shots he needed and boarded the S. S. Rijnstroom, a Dutch freighter, for his return.

The Rijnstroom was sunk by Nazi war planes. Borradaile escaped, but $16,000 worth of film went to the bottom of the North Sea. It's down there now.

Borradaile went back to Holland. People with cameras had grown less popular on that frontier. With great difficulty he obtained a permit. Suspicious police arrested him as soon as he began shooting. After his release and a lot of red tape he was guarded by a squad of soldiers and police. The guard attracted so much attention that crowds of curious Hollanders greatly hampered his work.

At last he finished, packed his film and took off for Bermuda. There he planned to ship the shots to the United States on the Atlantic Clipper, but the British censorship clamped down on the air mail and the film was blocked. It took Wanger weeks to get those scenes so vital to the picture.

There have been movies made before against tremendous technical odds, but I'm sure there's never been one before to come out of fabulous Hollywood like Foreign Correspondent, which has had to battle the most violent forces ever unleashed in the world.